Memes Are the Quintessential Postmodern Art Form

And it seems like there’s nowhere to go from here

Like most people my age, I spend a lot of time looking at social media, but I’m in it less for the “social” media as I am for the memes.

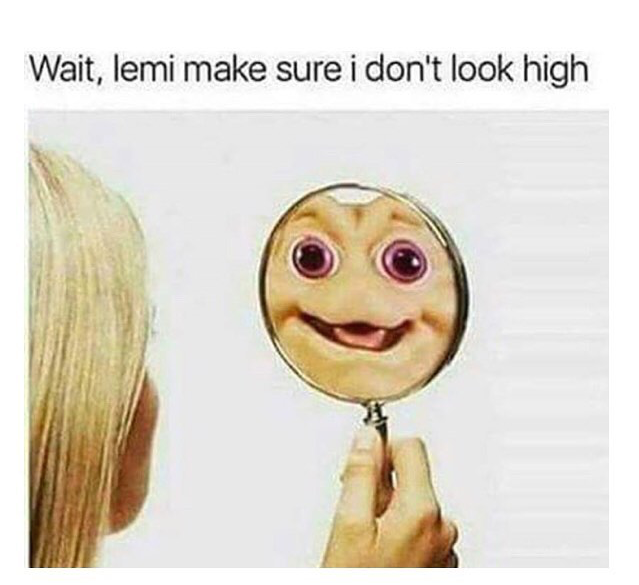

In the plainest terms, I’m a crackhead for them. I look at them intermittently the whole day long, and I catch myself doing it compulsively, almost subconsciously. One moment I’m working on something important, the next moment I’m reading words like “Stonks” and “Pupperino” and “Lämp” and my eyes glaze over as I become practically hypnotized by the bizarre, meaningless purgatory (or is it a heaven? a hellscape?) that is my meme-filled Instagram feed. The high I get from looking at a meme is paltry at best, and the effect wears off almost instantly. I keep chasing it anyway, and lately I’ve been wondering why that is.

Why are memes so unsatisfying, yet so addictive? Why do we gravitate towards them? And what does it say about us that memes have become one of our chief sources of entertainment?

The answer, I’ve found, is tied up in the idea of postmodernism. Memes, after all, are the quintessential form of postmodern art.

To refresh your memory — in case you’ve forgotten that long ago art history class — postmodernism is the 20th-21st century artistic movement broadly defined by irony, irreverence, intertextuality, self-reference, and meta-fiction, as well as a general attitude of skepticism, cynicism, and pessimism. Each of these qualities are inseparable from those captioned images and videos we have come to refer to as “memes,” and they provide insight into exactly why memes have come to tantalize us.

Irony

Irony, of course, is the basis of all meme humor (not to mention humor in general), and it is the only truly essential quality of a meme. Irreverence, intertextuality, self-reference, metafiction, pessimism… they are generally used within memes as a method of creating irony, “the expression of an idea using language which normally signifies the opposite meaning” or “something that runs contrary to our expectation.” Memes play upon our expectations to create humor, and the reason for this is actually rooted in the psychological mechanism and evolutionary purpose behind humor in general.

In their 2011 book Inside Jokes, researchers Hurley, Dennett, and Adams argue that humor evolved because it strengthens the ability of the brain to find mistakes in active belief structures. Humor is the pleasure of detecting mistaken reasoning. They address a wide swath of competing theories of humor, including “Benign Violation Theory,” which suggests that humor can only occur in the presence of three conditions:

- a moral violation threatens our sense of how the world “ought to be”

- the threatening situation is rendered benign

- we see both interpretations simultaneously

To put this in the simplest terms possible, imagine someone says something you don’t agree with, but they say it with a voice that indicates they are being insincere. That’s sarcasm. It was a moral violation made benign by the speaker’s intention, so you find the joke humorous. On the other hand, if the speaker is someone you disagree with, they might present your own opinion with sarcasm — now the statement doesn’t “threaten your sense of how the world ought to be,” but the speaker does. The situation isn’t rendered benign, and you’ll likely be more pissed off than entertained.

The measure of humor is the extent to which we can benignly subvert our expectations and preconceived notions. The pleasure of detecting mistaken reasoning, of learning, is achieved by this intellectual subversion, and it is through irreverence, intertextuality, self-reference, and metafiction that memes generally accomplish this effect.

Irreverence

Many memes are “irreverent” in the sense that they are deliberately crass, offensive, or perverse. We are shocked by the immoral perspective of the author or meme subject, but we recognize the sarcastic intent behind the immorality and thereby recognize it as benign.

Irreverence is extremely pervasive in memes, but usually it cannot stand alone. Something crass, offensive, or perverse is not often funny in and of itself, because in order for something to strike us as funny we need the absurdity which allows us to perceive the moral or intellectual violation as benign.

While both of the memes above are irreverent, neither of them depend solely upon irreverence. Each of them uses cross-references to fictional universes in order to create additional humor, and on that note…

Intertextuality

In literature, intertextuality is a deliberate and conspicuous relationship between two texts. One might think of Jorge Luis Borges, who within his own short stories made frequent references and allusions to other literary works like Don Quixote or The One Thousand and One Nights. One might also think of classic hip hop music, in which sampled audio creates an intellectual bridge between the source music and the resulting pastiche. Memes, similarly, rely upon cross-reference between a variety of sources, whether those sources be in the real world or the realm of fiction.

In the memes above, for example, we have the innocent children’s television character Arthur (a favorite of meme makers), captioned with a quote that changes him into a sexually exploitative drug dealer, and in a Star Wars reference, we have a Yoda quote placed in a context which reverses the meaning from innocent wisdom to comical perversity.

The examples above are only the tip of the iceberg, and other examples are far more complex. Rather than simply move a fictional character into an ironic context, many intertextual memes achieve a different effect by merging multiple fictional elements into a singular scene, changing the meaning of multiple fictional elements instead of just one.

Intertextuality also exists within the confines of meme culture itself, in the sense that memes reference other memes and create a pastiche out of existing meme tropes. Which brings me to my next topic:

Self-Reference and Meta-Fiction

In classic post modern art, self-reference emerged as a rejection of realism, which various artists believed to be fraudulent in its attempt to imitate and stand in for real life. The painting above by René Magritte, titled The Treachery of Images, seeks to express this concept by declaring beneath the image of a pipe “this is not a pipe.” The same rejection of realism became prevalent in literature as well, with many writers choosing to make their stories reference themselves as such. Consider the opening of Kurt Vonnegut’s crowning achievement Slaughterhouse Five: the narrator begins by saying “All this happened, more or less,” and he goes on to describe how he came to write the very novel you’re reading. The narrator deliberately reminds you that this is a fictionalized account of something real, that it should be regarded as art and not as the event itself.

Memes apply self-reference to a more extreme and less philosophical effect. Memes are inherently rooted in viral trends, and they create thematic, formal, or metaphorical structures within which they operate. The “Crying Jordan” meme is perhaps one of the simplest examples of a classic meme metaphorical structure. Obviously, Jordan crying represents sadness, loss, “taking an L,” et cetera, and so the meme revolves around placing Jordan’s crying face over the faces of people that have recently suffered some sort of defeat. In order to add humor and novelty to the repetitive joke, people will often deviate from the norm by photo-shopping Jordan’s face onto unexpected subjects, like in the following meme from the 2016 presidential election:

The Crying Jordan meme is one of the simplest examples, but self-reference in meme culture is extremely diverse and often hopelessly convoluted. Behind irony, self-reference is perhaps the most prevalent and definitive aspect of meme humor. A personal favorite of mine is the Kodak Black “can we listen to something else?” meme, which began with the following tweet by @IdiotOlympics:

The humor here comes from several sources. Kodak’s facial expression is funny and relatable in and of itself, and there’s also an irreverent humor in the idea of throwing your nagging passenger out of a moving car simply because they don’t like your music. The meme, however, would not be able to perpetuate itself solely by repeating this joke over and over. No one would laugh if we simply replaced “Future” with our own favorite artists. Subsequent iterations of the meme instead derived their humor through absurdity, creating ironic deviations from the formal structure which had already been created.

Similar examples of self-reflexive, meta-humor abound, as all memes are essentially based in some formal structure which can be remixed and subverted. Take, for example, the “Car Salesman” meme. It began in 2014, when twitter user @OBiiieeee tweeted the following:

Car Salesman: *slaps roof of car* this bad boy can fit so much fucking spaghetti in it

In 2016, the quote was re-posted, accompanied by the following image:

The meme all but disappeared, but then it exploded in the summer of 2018, with subsequent iterations all deriving their humor by commenting upon and diverging from the formal structure they were simultaneously helping to construct:

All of these memes derive their irony and humor exclusively from the viewer’s preexisting knowledge of the formal structure being employed. If we are unfamiliar with the meme, then there is no expectation for them to deviate from and no irony to be had. The last meme, above, is perhaps the most extreme example, in that it not only references the car salesman meme but also includes an intertextual reference to the “It’s Free Real Estate” meme. For the meme-obsessed, this makes it all the more humorous. For the uninitiated, it makes it all the more incomprehensible.

Skepticism, Cynicism, and Pessimism

The attitude of post-modern art is associated with disillusionment — a disillusionment with enlightenment ideals of human agency, social progress, the benefits of technology, and the rational nature of the universe. Post-modern art is predominantly nihilistic, favoring a view of reality in which humans are fragile, cruel, and pathetic creatures, social progress is moving in a largely negative direction, technology is a greater foe than friend, and the universe itself is a chaotic, irrational, and unsympathetic landscape. Memes, for the most part, seem to endorse this cynical and pessimistic outlook, although they frequently present these depressing ideals in an ironic fashion. In this way, it almost appears as if memes are trying to assuage our feelings toward meaninglessness.

In the meme above, minor inconvenience leads to contemplation of suicide. It is humorous in the sense that a minor inconvenience is obviously an absurd reason to consider suicide. Even though the meme reinforces the idea that suicide is a possible solution to our problems, it makes an argument that suicide is an absurd and illogical choice. The pessimistic message, since it is presented ironically, actually creates an optimistic effect on the viewer.

Perspectives of cynicism and pessimism are as prevalent in memes as they are in all of postmodern art, if not more so. Memes use these attitudes to a unique effect, however, because their constantly ironic presentation forces us to modify or reject the same pessimistic philosophy which forms the basis of the joke.

The Problem with Postmodernism

As we have seen, memes are not only valid examples of postmodern art but are arguably the definitive example. This may seem like high praise for memes, but before we start putting Shrek-Mike-Kermit images in the Louvre we should consider to what extent the popularity and ubiquity of memes is a good thing.

Memes are among the most frequently digested forms of art in the modern world, on the same level as music and film, and this may be a troubling notion when one considers how briefly and insignificantly they affect us and how inapplicable much of their humor is to real world problems. In our earlier discussion of irony, we presented the idea that the purpose of humor is to expose and correct examples of flawed reasoning — laughter is produced by an ironic form of education. The problem with memes is that, for the most part, they frequently reinforce our preconceived notions without offering any broader philosophical or intellectual message.

The above meme, for example, tells us absolutely nothing which might correct some form of flawed reasoning. All it does is acknowledge that giggle-fits are something that exist, and it pairs this notion with an image of Kardashian sisters laughing. Not all memes are this inane, but the trouble is that most memes tend to comment more on their own formal structure than on broader issues. The salesman memes, for example, are more funny than this one, but only because of an absurdity they create within their own paradigm. They do not alter our perspective on anything outside the realm of that particular meme.

The simplistic humor of memes coupled with their context-specific meanings give them a short shelf life. Once a meme has been seen once, it rapidly loses its ability to elicit laughter, because our cognitive web has already adjusted itself to incorporate the minuscule modification offered by the image. The memes everyone knows this week will be less humorous by next week. Most quickly lose their appeal and disappear. The car salesman meme, for example, lasted all of a month, and the Google Trends chart for “Slaps roof of car” perfectly demonstrates its rapid rise and fall:

Sometimes, though, a meme will stick around. This happens when a meme has a broad capacity for being remixed or when its longevity is, in itself, ironic. In the latter case, take the Shrek memes for example. There are a seemingly infinite variety of them, and part of the joke lies in the lingering nostalgia and borderline obsession with the random film from our collective childhood. The Shrek memes cannot die because their longevity is to an extent the ironic basis of the joke — the longer they go on the more the absurdity grows — but they cannot get better either… they can only tell the same joke in ever-stranger ways.

Every aspect of our pop culture, and by extension our entire society, has undergone what we might call meme-ification. The Kardashians are famously famous for being famous. The “Cash Me Outside” girl has a recording contract with Atlantic records. A reality TV star is president, and he was elected after riding a tsunamic wave of negative press coverage. In an era of short attention spans and cultural superficiality, attention becomes everything. To earn it, celebrities and artists must constantly be turning themselves into memes.

Drake is a master of the technique. Like a human meme, he has perfected the ability to remix his own formal structure. He is a chameleon, appropriating new rap styles and influences in order to become something novel, while never directly contradicting his original, essential persona. But that’s not all. He has even gone out of his way to explicitly meme-ify himself, making meme-conscious decisions in his music videos and promotions. With the video for his hit song Hotline Bling, he stated to his production team that he expected aspects of his dancing to be turned into memes, and, wisely, part of the subsequent release-day marketing for the video included paying popular meme accounts to inundate social media with Drake-dancing jokes and video remixes. The diversity and ubiquity of the memes became an extremely effective and low-cost marketing strategy.

Drake not withstanding, the problem suggested by meme-ification is not that our taste in art has become superficial or meaningless, but that our philosophy has. Our art is a reflection of our beliefs, and the reason we are now inundated with facile memes instead of “true art” is that we live in a world that is post-belief. We live in a world that is no longer evolving on a philosophical basis, a world that, for better or worse, is losing its religion and not finding anything to replace it with. Without the potential for radically new ideas, philosophies, belief systems, or ways of seeing the world that an artist might earnestly express and promote through “high art,” there is then less and less room for anything which is not ironic, superficial, pessimistic, and self-referential.

But if memes succeed in holding back that dreadful nihilism, if they can even partially assuage our depression and anxiety in a seemingly meaningless world, then perhaps they are more valuable than I am giving them credit for. Maybe a meme a day can keep the psychologist away. Or maybe not.

Either way, I know I can’t stop looking at them.